‘And give good tidings to the strangers’ [MADAMASR]

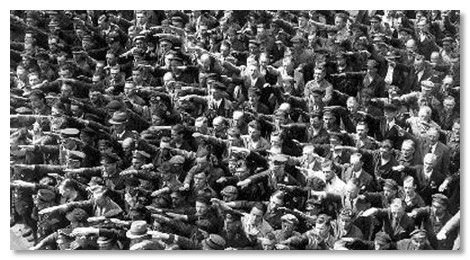

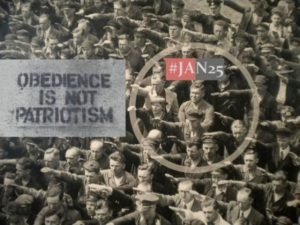

For years now, I’ve had an edited copy of a famous picture of a solitary German man standing in a crowd of Nazi supporters in 1935 as the background to my Facebook page. Surrounded by scores of presumably loyal backers of the Third Reich, who all appear to be offering the Nazi salute, he refuses to join them in that salute. He has clearly found himself in the crowd somehow — but he opts not to offer a stiff arm alongside them.Nearly 80 years later, I edited the picture. I put the red, black, and white logo of #Jan25 next to him, with the implication that what that man stood for had resonance for supporters of the January 25 revolutionary uprising as well. Nine years after the ouster of Hosni Mubarak — nine years after the beginning of many dreams — I continue to keep that same picture as a background, and often look at it. It continues to ‘work’ in terms of its resonance, at least for myself.The original picture is of August Landmesser, a German Christian in Nazi Germany who married Irma Eckler (a German Jew) in 1935. It has become etched into European historical memory as an example of someone who insisted on the right to say ‘no’ when the populism of the age seemed overwhelmingly in support of saying ‘yes’.The connection between the two historical moments may seem counter-intuitive; after all, Mubarak’s resignation was a popular demand, and a morally good one, unlike the popular demand of the German Nazi-supporting crowd.But the image of that individual protest touches a nerve with those who continue to support the January 25 revolution today.The analogy obviously isn’t with regards to the evils of Nazism. But there are correspondences with the notion of being almost friendless in a group, in the midst of massive populism aimed in another direction, placing great stress on that independent faction.There’s a phrase that I remember a good deal vis-à-vis that revolutionary movement, which became the title of an article published in the maiden days of this very publication, Mada Masr. It’s called “Back to the margins,” and it was written by Lina Attallah as the June 30 protests drew closer and closer. She encapsulated what many supporters of the revolutionary movement felt, which was that their discourse was being pushed further and further away from public discussion of the time. The two main factions in the run-up to the protests were those who supported the Morsi government and those who supported overthrowing it by any means necessary. Those who failed to fit neatly into either category were, indeed, on “the margins.”As for the “back to” part of the article’s title, it was a reminder that for much of the January 25 movement’s active lifespan, it was on the margins. Indeed, that same movement may have been named “25th of January” in 2011, but it existed long before then. It never held power, and for much of its history, it was on the periphery and the margins.It had influence at particular points, yes — especially during the uprising itself in 2011 and thereafter. I wrote about some of those points in my book on the uprising and its aftermath, entitled A Revolution Undone: Egypt’s Road Beyond Revolt, and the “undone” hints at that in particular. It didn’t mean a revolution had been done, and then became dismantled — rather, that the revolution hadn’t been completed. It had been left undone, unfinished, incomplete. That meant work still had to be done — and that remains true today.Different populist waves continue to cause so much damage in our time — not only in Egypt, but in other countries as well: across Europe, America, Asia — I’ve lost count. The oppression of Rohingya and the Uyghurs, the rise of Trump, the mainstreaming of the European far right. These are clearly all different, and I don’t mean to underestimate any one of them by comparing them to any other. But the underlying commonality is simply this: that evil happens when goodness is reduced merely to love for one’s country or community, and when principles are sacrificed on the altar of the same. It’s a message that Landmesser clearly rejected.There was a time I wondered if the specificity of the Jan 25 logo was somehow self-defeating. Because, clearly, the uprising itself succeeded in 2011, while the revolution did not. I’m not of those people who insist on pushing the narrative of the revolution as failed, because the reality of history is that revolutions are judged and assessed over much longer periods of time than a few years.But be that as it may, the logo created a locus of historical centrality to this particular event — the uprising in 2011 — and that makes it time bound, and thus limited. Good friends have expressed fear that to look back on this time as such is to invite the fate of becoming a relic of the past themselves: has-beens, “we were the future once”, and so on.I see it somewhat differently. Because if the point of remembering is to simply be stuck in stasis, and to fail to do anything beyond basking in memories, then yes: it’s self-defeating indeed.But I’ve never seen the revolutionary uprising and its symbol of #jan25 in that fashion. On the contrary: The very act of remembering is an act of defiance against a system, as well as systems that have been put into place to deny that #Jan25 ever existed.Remembering doesn’t need to be an act of defiance for the sake of it, just to be contrarian. Nor to simply publicly declare one’s principles in the face of crowd pressure. That is powerful in and of itself — but more powerful still is having that act of remembrance as a starting point for living one’s life in ways that reject the normalization of different types of authoritarian notions which have become part of the status quo, irrespective of whether they spring from radical religious ideas or populist autocratic ones.What links defiant memory to that revolutionary moment nine years ago is perhaps that two-fold emphasis on remembering the past, but peering forward: moving onward with the benefit of lessons learned, while recalling the intentions that drove us to those streets. To forget those intentions is to betray a part of ourselves that remains committed to insisting that justice and mercy be the twin bases of our social relationships.The symbol carries a twin emotional effect: it will forever strike a chord of angst in the oppressor. To this day, every year that #Jan25 comes along in the calendar, there is grave anxiety among those who insist that brute force and fear are the blocks of some odd grotesque version of “stability” in society. In reality, those blocks are merely increasing its core instability.Moreover, it strikes a note of hope for the oppressed, especially for those who lived through the uprising, that is at least in part inspired by the people and the stories one encountered back then.It is difficult to be friendless in a crowd; it can be difficult to be on the margins. I am reminded of this particular verse: “…فَطُوبَى لِلْغُرَبَاءِ ”

For years now, I’ve had an edited copy of a famous picture of a solitary German man standing in a crowd of Nazi supporters in 1935 as the background to my Facebook page. Surrounded by scores of presumably loyal backers of the Third Reich, who all appear to be offering the Nazi salute, he refuses to join them in that salute. He has clearly found himself in the crowd somehow — but he opts not to offer a stiff arm alongside them.Nearly 80 years later, I edited the picture. I put the red, black, and white logo of #Jan25 next to him, with the implication that what that man stood for had resonance for supporters of the January 25 revolutionary uprising as well. Nine years after the ouster of Hosni Mubarak — nine years after the beginning of many dreams — I continue to keep that same picture as a background, and often look at it. It continues to ‘work’ in terms of its resonance, at least for myself.The original picture is of August Landmesser, a German Christian in Nazi Germany who married Irma Eckler (a German Jew) in 1935. It has become etched into European historical memory as an example of someone who insisted on the right to say ‘no’ when the populism of the age seemed overwhelmingly in support of saying ‘yes’.The connection between the two historical moments may seem counter-intuitive; after all, Mubarak’s resignation was a popular demand, and a morally good one, unlike the popular demand of the German Nazi-supporting crowd.But the image of that individual protest touches a nerve with those who continue to support the January 25 revolution today.The analogy obviously isn’t with regards to the evils of Nazism. But there are correspondences with the notion of being almost friendless in a group, in the midst of massive populism aimed in another direction, placing great stress on that independent faction.There’s a phrase that I remember a good deal vis-à-vis that revolutionary movement, which became the title of an article published in the maiden days of this very publication, Mada Masr. It’s called “Back to the margins,” and it was written by Lina Attallah as the June 30 protests drew closer and closer. She encapsulated what many supporters of the revolutionary movement felt, which was that their discourse was being pushed further and further away from public discussion of the time. The two main factions in the run-up to the protests were those who supported the Morsi government and those who supported overthrowing it by any means necessary. Those who failed to fit neatly into either category were, indeed, on “the margins.”As for the “back to” part of the article’s title, it was a reminder that for much of the January 25 movement’s active lifespan, it was on the margins. Indeed, that same movement may have been named “25th of January” in 2011, but it existed long before then. It never held power, and for much of its history, it was on the periphery and the margins.It had influence at particular points, yes — especially during the uprising itself in 2011 and thereafter. I wrote about some of those points in my book on the uprising and its aftermath, entitled A Revolution Undone: Egypt’s Road Beyond Revolt, and the “undone” hints at that in particular. It didn’t mean a revolution had been done, and then became dismantled — rather, that the revolution hadn’t been completed. It had been left undone, unfinished, incomplete. That meant work still had to be done — and that remains true today.Different populist waves continue to cause so much damage in our time — not only in Egypt, but in other countries as well: across Europe, America, Asia — I’ve lost count. The oppression of Rohingya and the Uyghurs, the rise of Trump, the mainstreaming of the European far right. These are clearly all different, and I don’t mean to underestimate any one of them by comparing them to any other. But the underlying commonality is simply this: that evil happens when goodness is reduced merely to love for one’s country or community, and when principles are sacrificed on the altar of the same. It’s a message that Landmesser clearly rejected.There was a time I wondered if the specificity of the Jan 25 logo was somehow self-defeating. Because, clearly, the uprising itself succeeded in 2011, while the revolution did not. I’m not of those people who insist on pushing the narrative of the revolution as failed, because the reality of history is that revolutions are judged and assessed over much longer periods of time than a few years.But be that as it may, the logo created a locus of historical centrality to this particular event — the uprising in 2011 — and that makes it time bound, and thus limited. Good friends have expressed fear that to look back on this time as such is to invite the fate of becoming a relic of the past themselves: has-beens, “we were the future once”, and so on.I see it somewhat differently. Because if the point of remembering is to simply be stuck in stasis, and to fail to do anything beyond basking in memories, then yes: it’s self-defeating indeed.But I’ve never seen the revolutionary uprising and its symbol of #jan25 in that fashion. On the contrary: The very act of remembering is an act of defiance against a system, as well as systems that have been put into place to deny that #Jan25 ever existed.Remembering doesn’t need to be an act of defiance for the sake of it, just to be contrarian. Nor to simply publicly declare one’s principles in the face of crowd pressure. That is powerful in and of itself — but more powerful still is having that act of remembrance as a starting point for living one’s life in ways that reject the normalization of different types of authoritarian notions which have become part of the status quo, irrespective of whether they spring from radical religious ideas or populist autocratic ones.What links defiant memory to that revolutionary moment nine years ago is perhaps that two-fold emphasis on remembering the past, but peering forward: moving onward with the benefit of lessons learned, while recalling the intentions that drove us to those streets. To forget those intentions is to betray a part of ourselves that remains committed to insisting that justice and mercy be the twin bases of our social relationships.The symbol carries a twin emotional effect: it will forever strike a chord of angst in the oppressor. To this day, every year that #Jan25 comes along in the calendar, there is grave anxiety among those who insist that brute force and fear are the blocks of some odd grotesque version of “stability” in society. In reality, those blocks are merely increasing its core instability.Moreover, it strikes a note of hope for the oppressed, especially for those who lived through the uprising, that is at least in part inspired by the people and the stories one encountered back then.It is difficult to be friendless in a crowd; it can be difficult to be on the margins. I am reminded of this particular verse: “…فَطُوبَى لِلْغُرَبَاءِ ”

“‘And give good tidings to the strangers.’ And when he was asked, ‘who are the strangers’, the Prophet is reported as having responded: ‘Those that correct the people when they become corrupt.’ In another verse, he said, ‘They are a small group of people among a large wrong population. Those who oppose them are more than those who follow them.’”It’s sometimes lonely to feel that strange. Many of my generation have been traumatized because of that time and the subsequent feeling of loneliness, and the inability to process it.But: give good tidings to the strangers. Not because they harken back to a time of glory, but because they hold fast to principles that are hard to uphold. In the end, it’s not about success — for that’s always out of our hands. It’s about the intentions we have, and doing what we can, truly, to bring them to fruition.Source: Mada Masr