Powerful Scholars and Clerics of Power: Remembering Shaykh Emad Effat [JADALIYYA]

Jan 26, 2021“I urge everyone, especially my students, to pause and reflect. The gauge is not the success of the revolution but taking a stand. Revolutions can be aborted, and sincere calls can be defeated. Some prophets, peace be upon them, will come alone on the Day of Judgment, some were killed, and that is not a measure of failure. Not at all; the gauge is one’s stand.”- Shaykh Emad EffatEmad Effat would have probably been a name known internationally to very few for much of his life. He didn't seek the spotlight, and he was content to fulfill his duties as a respected Azhari religious scholar. But when he died—when he was murdered—at the end of 2011 in Egypt, his memory became immortalised. It’s been a little over nine years since his passing, and ten since the Egyptian revolutionary uprising that he so deeply believed in, and a decade on, he represents so much. As much due to what he refused to do, out of principle, as what he did do, out of conviction.His story means something not only to Egyptians, as a revolutionary figure but, to Arabs in the region more generally, and to Muslims worldwide, as an example of a figure who refused to allow the religious discourse of his faith be used and abused by the machinations of state apparatuses on the one hand, and parochial movements on the other. Be it Cairo, Ankara, Doha, Abu Dhabi, or Riyadh, to name a few, various state actors, in addition to non-state actors, freely instrumentalise religion and religious discourse as part of their public diplomacy efforts. Indeed, in ways that are not bereft of power plays, to say the least, and not in the pursuit of any real ethical mission beyond a narrow definition of “national interest.”It's an interesting critique, because while we can certainly note that this type of instrumentalisation is something various political groups have been and continue to be guilty of, it is, let us say, a rather equal opportunity exercise, especially when we consider different regimes in the region. At this time when the wider Middle East and North Africa region is so insistent on demanding that one must line up with one power axis or another, Shaykh Emad shows a different kind of approach—one that is from the “marginal, maverick middle.”[1]

The Man

Effat, a deeply loyal and committed Egyptian through and through, came from a rather intriguing background. Those close to him allude to a younger phase in his life, where his politics were more radical, more revolutionary, though always non-violent. As a young man, nevertheless, he eventually was influenced into pursuing a different path, holding to an entirely normative Sunni interpretation of its religious tradition, as informed by his Azhari training. That led him to teach in the Azhar mosque, the symbolic seat of the Azhari establishment, which is the pre-eminent Sunni religious establishment worldwide. Most significant of all, he was a senior official of Dar al-Ifta’ al-Misriyya—the "Egyptian Abode of Edicts," where specialists in Islamic jurisprudence gave expert opinions on a vast variety of issues within a Muslim's personal life.Perhaps that younger, more "radical" phase perhaps immunised Effat from deleterious effects later in life, as he navigated the vagaries of the Egyptian official establishment. Because he most certainly was a part of Egyptian officialdom: Dar al-Ifta’ is a state institution and is situated under the jurisdiction of the Egyptian Ministry of Justice. Many of these “post-colonial” states insist upon certain narratives—true or false—and if one rejects those narratives, it's exceedingly difficult to continue operating within those establishments. The cognitive dissonance would be too great. Slowly but surely, the psychological narrative of a house of cards is built. Often—perhaps almost always—without the genuine recognition of how fragile that narrative is among those who hold it.

Shaykh al-Thawra: the Shaykh of the Revolution

One might have imagined, therefore, that when the Egyptian revolutionary uprising of 2011 came about, Shaykh Emad Effat would be among those religious figures who supported the state and opposed the uprising as a source of civil strife (fitna) and unlawful (haram). But he wasn't. Effat, for whatever reason, had escaped being conditioned by such narratives from the outset of his career in the state machinery, and despite his position, wasn’t among those pro-state members of the religious establishment. Instead, he himself went to Tahrir Square, in the centre of his country's capital, and participated in the protests as simply an Egyptian who loved his country.It is even more striking that he did so when one considers that both the institution he worked for, and the mufti of the time, were deeply opposed to the protests. As written by a student of Effat’s:“He never asked my opinion on going down to [Tahrir] square,” said the grand mufti, “He blamed me for not going there myself. He would say of it: ‘the air around Tahrir now, is purer to me than the air around the Kaaba.’”His widow, Nashwa Abdel-Tawab, said, “During sit-ins at Tahrir Square [in January and February of 2011, when the revolutionary uprising broke out], he would go to work in the morning and spend the night in the square.” Shaykh Emad believed in that revolution — as a way to “enjoin the good and forbid the evil,” as the Qur’anic verse stipulates. During the day, he would continue his work, as a part of the official state apparatus. And at night, he went to Tahrir Square, and called for accountability of that same state apparatus. He saw no contradiction in that—but he did so based on principle.

Husayn and Hasan

Muslim scholars of Islamic history can identify three types of approaches to political authority that had been deemed to become unjust. The first was that of Imam Husayn, the grandson of the Prophet, who openly defied the tyranny of his day. The second was that of Imam Hasan, who opposed injustice, but did so without open defiance, out of concern that such openness would lead to even more injustice due to resistance from the tyrant—though he would not normalise that tyrant beyond what was absolutely necessary to protect the vulnerable. The final category would be those who accept the narrative of the tyrant as normative in and of itself. Shaykh Emad, arguably, exemplified particularly the Husayni approach, and sometimes the Hasani—but on a religious basis, he rejected normalising the narrative of unjust political authorities.His upholding of that Husayni tradition continued past the uprising, which the following story narrated by Waleed Almusharaf elucidates:Among the last conversations that [Shaykh Emad] was to have, perhaps two weeks before his death, was one overheard by Tarek as he sat in the shaykh’s office at Dar il-Ifta.A man called asking for a fatwa, a non-binding legal opinion from Sheikh Emad, Tarek told me. He wanted to know if it was permissible according to the Sharia, for a police officer or other government official to fire upon protesters. “No,” said Shaykh Emad. “And if they are attacking the police with rocks?” The man asked. “No.” “And if they are destroying property and causing damage?” “No.” “What if they are causing civil strife among them Muslims,” the man said, invoking the most grievous of social acts in the religion. “No.” “Is there any circumstance where perhaps a police officer is entitled to shoot at a civilian?” “In theory,” Shaykh Emad said to the man, “It is possible that there is a circumstance where an officer may shoot a civilian, non-lethally, but I, for one, will give no such opinion.”That kind of insistence on maintaining a deeply ethical worldwide, rooted in a sense of justice, opposing particularly state-led injustice, is what made Effat so striking—at a time when so few within different religious establishments seem keen to do the same. Indeed, that temptation to normalise injustice—from within religious establishments—is particularly common nowadays, and has little in common with the Husayni or Hasani imperatives Effat upheld.

Religion Merchants

There is another interesting aspect to Shaykh Emad, and that was his opposition to certain Islamist groups in Egypt. Of course, as one might reasonably assume, he opposed extremists like al-Qaeda (the so-called Islamic State group hadn't yet become a reality). But he was also deeply antipathetic to how more mainstream Islamist groups of the day were instrumentalising religion for purposes he saw as unethical.Ibrahim al-Houdaiby, a noted revolutionary activist and commentator in Egypt, once tweeted about the deaths of mainly Coptic protesters in Cairo at the hands of state forces, during the infamous Maspero massacre which took place in October 2011, only weeks before Effat was killed. Al-Houdaiby declared that any talk which does not begin with the condemnation of the massacre, was “an affront to humanity and patriotism.” Shaykh Emad, who tweeted nine times in his life, added, “And to religion.”That was the place of religious vocabulary in Shaykh Emad’s lexicon—to stand for truth against power, not in trying to explain away the abuses of power through verbal gymnastics. He was clear about that when it came to the Egyptian state—even though he worked in one of its institutions—and he was clear about it when it came to sectarianism. The Maspero massacre was nothing if not a sectarian outrage—perpetrated by state institutions and defended at the time by right-wing populists such as within the Muslim Brotherhood, hardline nationalist groups, and others. Not Shaykh Emad.In the year that Effat lived through the revolutionary period of Egypt, it was clear his politics, informed by his ethics, rooted in his religious worldview, insisted on one thing—reject injustice, whether it was promoted via nationalism, or religious rhetoric. That made him many friends among the revolutionary camp; not so many among supporters of Mubarak, nor, at least during his lifetime, of the Brotherhood contingent of the day, who had chosen a particular trajectory of engagement with the military, which ended in catastrophe.

His Spirit Rose

On 19 December 2011, military forces guarding the Cabinet building near Tahrir Square, tried to forcibly remove a small sit-in that had been set up there. The sit-in was a protest against the continuing holding of power by the military, demanding that executive authority be transferred to civilians. When Effat heard of the effort to forcefully remove the sit-in was ongoing, he went in solidarity with the sit-in. He was dressed as a normal Egyptian citizen, as he always was in protests, rather than in his Azhari gear; he generally preferred to participate in such things not as a representative of an institution. No investigation ever found the culprit, but in 2012, there was no doubt expressed about the conclusion that the security forces had shot him in the midst of the crackdown. Waleed Almusharaf’s testimony from the time reveals as such:“After the bullet had passed through the body of Sheikh Emad Effat, his body hit the ground, and his spirit rose to meet its Lord. A short while after that the caller called for the sunset prayer, and night fell on a Friday in December. His family and friends, his teachers, his students, and many others who did not know him mourned him. They and others felt towards him something else also which wasn't mourning but which shared with mourning something sad and something fierce, and something else which I didn't yet know, and I was one of those. All this is beyond dispute.And yet, that night, in the tiny clearing in front of the morgue, under the sad yellow lights, there was a dispute. His family and friends, among them a woman wearing a scarf on her head who if I remember correctly was his wife, wanted Dar al-Ifta’ to tell the world how he was shot, and who it was who was standing next to him, and carried him, whose hands were drowned in his blood, and who tried to save him. Above all, they wanted them to say where he was when he was shot, and why. Why he was there, and why he was shot.”Yet, doubts were sown a great deal thereafter, and some tried immediately after the event. “Fake news” and misinformation aren’t just Trump phenomena. In the heady days after the overthrow of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi in 2013, reports from authorities on the radio in Cairo declared that they "finally knew" who killed Shaykh Emad. It was, of course, the Brotherhood. Such a conclusion was preposterous, including to long time critics of the group; but it was just another in a long line of examples of how the truth itself became a victim.

Mourning Across Boundaries

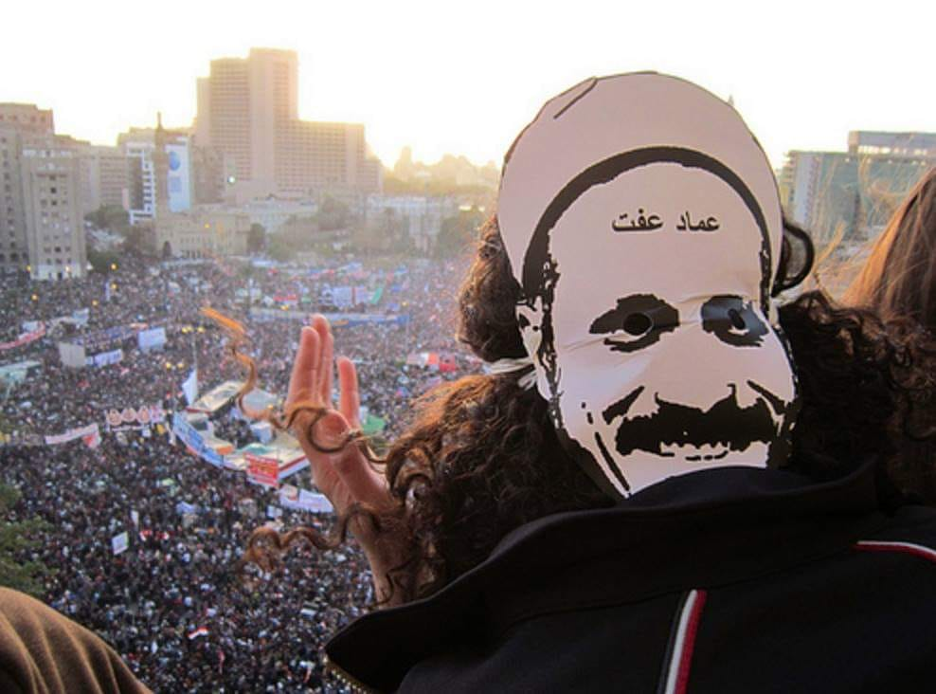

A month later, a celebration for the first anniversary of the uprising. Despite the tumultuous events of the year, there was a fighting spirit the crowd. The free Syria flag was being flown high; people continued to support neighbours to the west in Libya, who had overthrown their dictator; and many still thought they had a chance to bring the promise of the revolutionary uprising to fruition in a way that would match, if not exceed, what came to pass in Tunisia. It wasn't to be.A decade on, it isn't that the uprising meant nothing—it meant a great deal and had lasting effects—but when zero-sum games come into play, everyone loses. A recent public discussion on the Arab uprisings with South African activists, veterans of the anti-apartheid struggle, at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, made the point clearly—if the struggle is to have lasting consequences, it has to reject the zero-sum game. You have to find ways to make it so that as many as possible win, and as few as possible lose. Otherwise, the spoilers wreck it all.

Axes, Geopolitics—The Lot of Them

One of the main reasons Shaykh Emad’s example continues to resonate is because of how rare he was as a member of the religious establishment. When one looks at the geopolitics of the region following 2011, there is much to observe, but one of the most fascinating, because of its transnational impact, is how religious geopolitics of the region have played into the basic divisions. Prior to 2011, it was mostly about Sunni Saudi versus Shi’i Iran one could find analysis about. Post-2014, there were new axes to consider—particularly the Egyptian-Emirati-Saudi on the one hand, and the Turkish-Qatari on the other.Ironically, the religious confessions that one might interrogate cut across them; a more historically traditional Sunnism is to be found in the establishments of Turkey, Egypt, and the UAE, while Qatar and Saudi share different interpretations of purist Salafism. But each power deploys specific readings—usually very modern and novel readings—of their religious heritages to buttress their power-political agendas and control.And those agendas are not limited to their own countries, nor to the MENA region. They went global—including within the West. Different parts of both of those axes have already invested a great deal of time and effort to further their "soft power" among significant Muslim religious figures and institutions in the UK, the US, and elsewhere. Opposition to that is usually expressed in a rather partisan fashion:supporters of Ankara will decry those who are influenced by the UAE, often with great and important justification; but will say nothing about their own links to Ankara. Those influenced by the other axis will make critiques of the other side; but too rarely will come out against the deleterious impacts of their own axis, of which there are many.It’s uncertain how Effat might have navigated those religious-political axes—but consistent with his approach while alive would have been a respectful distance from all those axes, while critical of the lot of them. And probably, he would have been accused by both of being in league with the other side—because that's the easy way out for the lazy partisan critic.

Perhaps what is coming is harder than what has passed

There is something deeply significant and symbolic about Shaykh Emad; someone who truly embodied a lot of the complexity of the Egyptian revolution of 2011. As the 10th anniversary of the January 25 uprising is reached, it's clearly the case his hopes were dashed. Yet, his words to Ibrahim al-Houdaiby continue to ring true:I urge everyone, especially my students, to pause and reflect. The gauge is not the success of the revolution but taking a stand. Revolutions can be aborted, and sincere calls can be defeated. Some prophets, peace be upon them, will come alone on the Day of Judgment, some were killed, and that is not a measure of failure. Not at all; the gauge is one’s stand.Do not look at the consequence of what has happened but look at its nature and what it was. What was your position? Where were you? Why were some of us present in classes and at prayers, but absent at these blessed moments? We must reassess and hold ourselves accountable because God, with His mercy, extended our lives, and so this is an opportunity to re-evaluate. As long as we breathe there is room for repentance and revision. The end is the gauge. It is not too late. Perhaps what is coming is harder than what has passed.